Therapy for Depression

We’re happy you’re here. Depression can present in our bodies in several ways – and with each individual’s unique experiences – there are multiple ways we can work together to address the symptoms and behaviors you’re experiencing. Many individuals who are depressed report symptoms of fatigue, hopelessness, feelings of emptiness, irritability, and more. Depression can feel like not wanting to get out of bed, overeating or under-eating, fixating on past failures or self-blame, and having trouble concentrating, making decisions, and remembering things. Depression can also cause foggy thinking, slowing down our speaking or body movements, and even unexplained physical aches, such as back pain or headaches. Please know that this is not an all-encompassing list, and each person brings their own unique experiences to the space. Individuals who are feeling symptoms of depression may also experience suicidal ideation and have urges to self-harm.

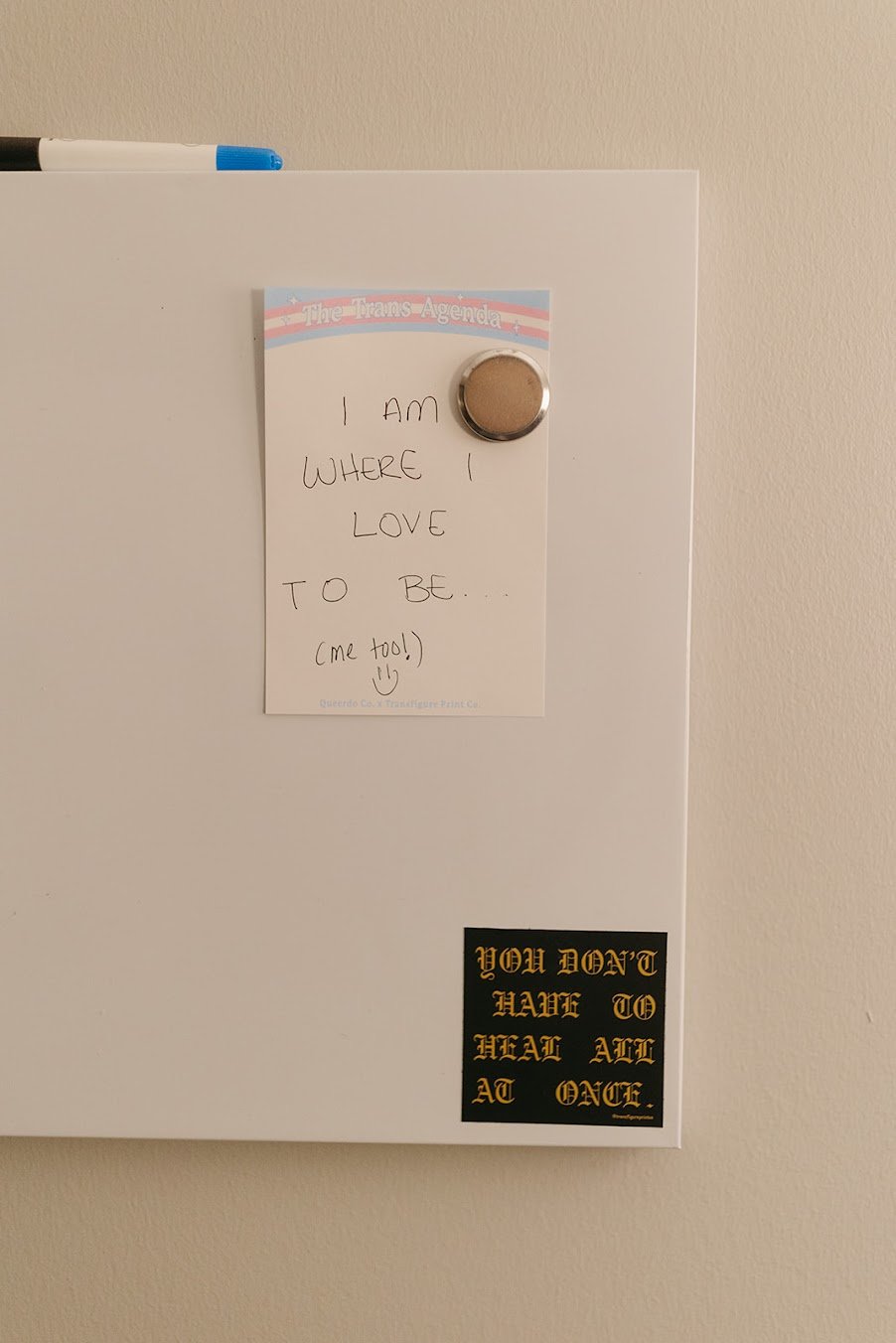

Given the minority stressors queer, trans, and gender-expansive individuals face, we are at a higher risk of experiencing these symptoms of depression, self-harm, and suicidal thoughts. Minority stressors may include the expectation of rejection, identity concealment, the experience of prejudice events, internalization of negative societal views of LGBTQ status, and more. The levels and severity at which individuals experience minority stressors predict mental health outcomes [1].

Our clinicians operate through gender and neuro-affirming frameworks and work from an attachment-based lens, which can be helpful for understanding the root causes of depression. Depressed feelings are just one part of our larger internal system – and by processing and recognizing this – you can learn to develop a more compassionate relationship with yourself, relieving yourself of harsh judgments often associated with depression. We also keep in mind the capitalistic and oppressive systems many of us queer folks must operate within, and we will support you in identifying patterns and help you build knowledge and skills to support your goals. Learn more about the modalities we integrate into our practice below.

Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT)

DBT, developed by Marsha Linehan, is an evidence-based treatment that teaches individuals skills to manage intense emotions, cope with challenging situations, and improve relationships. DBT is proven to be helpful for individuals with suicidal ideation, self-harm, borderline personality disorder, negative body image, eating disorders, substance use, anxiety, and depression.

DBT has four primary skills: mindfulness, interpersonal effectiveness, emotional regulation, and distress tolerance. It is a skill-based approach based on dialectical and biosocial theory that emphasizes the role of difficulties in regulating emotions, both under and over control, and behavior [2].

At Grounded Wellbeing, DBT is offered in group and individual settings. It’s important to note that DBT was developed in the 1970s, and the modality has been adapted over the years. In addition to traditional DBT, at our practice, we’ve also started Queering DBT – a neurodivergent-friendly DBT group for queer, trans, and gender-expansive individuals. Queering DBT still highlights some of the key modules of traditional DBT while also adding coping skills for sensory-related issues. This way, neurodivergent folks wanting to learn the skills can do so in a way that supports the unique neurodivergence experience. In addition, Queering DBT takes into consideration the heteronormative language in the skills sheets.

DBT can also be weaved into individual settings with your clinician, especially if you want to work on a specific focus area, like mindfulness or distress tolerance. DBT might be a good fit for you if you're looking to change behavioral, emotional, thinking, and interpersonal patterns associated with problems in living.

Interested in joining a weekly DBT group? Reach out to us!

Mindfulness-Based Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT)

Developed in the 90s by Steven Hayes, ACT is a mindfulness-based behavioral therapy that uses “metaphors, paradox, and mindfulness skills, along with a wide range of experiential exercises and values-guided behavioral interventions” [3]. The method is based on a “pragmatic philosophy of science called functional contextualism” [4], which is a concept that focuses on the behavior of individuals within their historical and situational contexts. This methodology centers each individual’s unique experience, and takes into account the contexts in which you operate – socially, economically, spiritually, and more.

There are 6 core principles to help clients develop psychological flexibility: 1) cognitive defusion, 2) acceptance, 3) contact with the present moment, 4) the observing self, 5) values, and 6) committed action. With the ACT approach, the goal of healthy living is, “not so much to feel good as to feel good” [4], meaning that it is “psychologically healthy to have unpleasant thoughts and feelings as well as pleasant ones, and doing so gives us full access to the richness of our unique personal histories” [4]. ACT acknowledges that thoughts and feelings are interesting and important, but they should not necessarily dictate what happens next. Further, the specific role and importance we assign to a thought depends on the psychological context in which they occur. Framing our thought patterns through this lens is more flexible than any “normal problem-solving mode of mind” can assume [4].

In the therapeutic context, ACT focuses less on psychiatric symptoms and diagnoses than many other modalities and veers away from the diagnosis-centered medicalization of mental health. This method helps both the clinician and client “develop the essential qualities of compassion, acceptance, empathy, respect, and the ability to stay psychologically present even in the midst of strong emotions” [3].

If this approach interests or resonates with you, feel free to schedule your free phone consultation.

Internal Family Systems (IFS)

Internal Family Systems (IFS) is an attachment focused, and evidence-based modality that helps people heal by, “accessing and healing their protective and wounded inner parts. IFS creates inner and outer connectedness by helping people first access their Self and, from that core, come to understand and heal their parts” [5]. This model recognizes that we all have parts and that sometimes we live and lead from these parts when they become “blended” with Self. This modality aligns closely with our values, and the foundation of our practices. Attachment and relationally-based therapy are at the foundation of what we do. We honor the unique narratives that each individual brings, valuing the intersections of identity and relationships.

At the core of IFS is the idea of accessing your true Self by understanding all of your parts, growing compassion for them, and working to transform them. There are various aspects of IFS, and our inner parts can be categorized into managers, firefighters, and exiles, which all present in our bodies differently. These parts are influenced by past experiences, including trauma and adverse childhood experiences. We see parts for the value and adaptive strategies they have brought to our lives. Many of these parts have helped us survive challenging experiences. Through this work, we’re able to meet them with gentle curiosity and compassion as we explore their utility in our lives.

Often, we operate from parts other than Self, which can result in behaviors and emotions we are seeking to change or learn more about. For example, our manager likes to maintain control of its inner and outer environments by distancing ourselves from others we feel too close to, criticizing ourselves to make us feel, look or act better, and focusing on taking care of others' rather than our own [1]. The manager’s role is to keep us from feeling hurt, shame, embarrassment, and any of the difficult feelings that come with these emotions. These “hidden” parts are our exiles. The final part that comes up is the firefighter, who jumps into action, “whenever one of the exiles is upset to the point that it may flood the person with its extreme feelings or make the person vulnerable to being hurt again” [5]. Our firefighters are highly impulsive and strive to find stimulation that will override or dissociate from the exile's feelings.

Ultimately, IFS creates an understanding of personal and intimate relationships by stepping into life with the 8 Cs: confidence, calm, compassion, courage, creativity, clarity, curiosity, and connectedness [1]. You can read more about IFS, and the evolution of the modality, here.